Women are about twice as likely as men to experience a major depressive episode. Because this gender gap emerges in adolescence and persists until menopause, we speculate that some women are more vulnerable than others to the reproductive hormonal shifts that take place during the course of a woman’s reproductive life. Increased vulnerability to depression coincides with the premenstrual phase of the menstrual cycle, where about 5% of women experience premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), the postpartum period, and during perimenopause.

Another subgroup of women with hormonal sensitivity are women who experience mood changes or depressive symptoms after initiating treatment with a hormonal contraceptive. Many have speculated that women with sensitivity to hormonal contraceptives may be more vulnerable to depression at other times of hormonal transition, including the postpartum period. While the hypothesis that women with sensitivity to hormonal contraceptives may also be more vulnerable to postpartum depression is certainly plausible, it has not been carefully studied.

To determine whether prior depression associated with hormonal contraception is a risk factor for PPD, a recent study analyzed data from the Danish health registry, a cohort including 269,354 first-time mothers. Women were excluded if they had never used hormonal contraception or if they had a depressive episode within the year prior to delivery. Cases of postpartum depression were defined as the filling a prescription for antidepressant medication or receiving a hospital discharge diagnosis of depression within 6 months of childbirth.

In this cohort of 188,648 first-time mothers:

- 5722 (3.0%; mean [SD] age, 26.7 [3.9] years) had a history of HC-associated depression

- 18 431 (9.8%; mean [SD] age, 27.1 [3.8] years) had a history of non-HC-associated depression

- 2457 women developed PPD, corresponding to an incidence rate of 1.3%

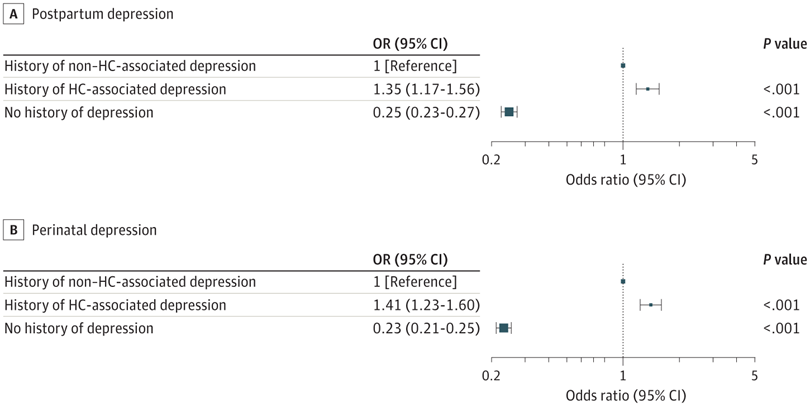

- Women with HC-associated depression had a higher risk of PPD than women with prior non-HC-associated depression (adjusted OR, 1.35 [95% CI, 1.17-1.56]).

Important Note: This study looks only at women who received pharmacologic treatment or were hospitalized for PPD. Thus, rates of identified PPD in this study are low compared to other studies that use questionnaires, such as the EPDS, to identify women with PPD. Cases of PPD in this study most likely represent only women with greater severity of depressive symptoms.

Some Other Interesting Findings

The researchers observed that women with HC-associated depression had more depressive episodes than women with non–HC-associated depression; 63.4% of the women with HC-associated depression had more than one episode of depression, compared to 38.6% of the women with non-HC-associated depression. Future studies are needed to determine whether there may be other clinical or demographic variables which distinguish women with HC-associated depression from those with non–HC-associated depression.

Although this study shows that having a history of HC-associated depression appears to be a risk factor for PPD, the risk associated with non-HC-associated episodes of depression is also very high, when compared to the magnitude of risk observed in women with no history of depression (See Figure 2, above). Put more succinctly, risk for PPD in women with no history of depression was about 0.9% in this study. In women with a history of any type of depressive episode (associated with HC or not), risk for PPD increases to 4.0%. That represents about a 4.4-fold increased risk for PPD. If depression was associated with HC use, the risk for PPD was 5.8-fold higher than observed in women with no history. If depression was not associated with HC use, the risk for PPD was about 4.1-fold higher. Thus, history of depression represents one of our strongest predictors of risk for PPD.

Clinical Implications

The findings of this study suggest that a history of depression associated with the use of hormonal contraception may be a risk factor for PPD, supporting the hypothesis that some women are uniquely vulnerable to reproductive hormonal shifts and thus may be more vulnerable to depression at times associated with shifts in the reproductive hormonal milieu. While it makes sense to ask if a woman has had an episode of depression associated with the use of hormonal contraceptives, women who have had episodes of depression not associated with the use of hormonal contraceptives also have a high risk of developing PPD.

Because this study defined PPD as the filling a prescription for antidepressant medication or receiving a hospital discharge diagnosis of depression within 6 months of childbirth, this study focused on the prevalence of more severe episodes of PPD. Further study is indicated to better understand the link between HC-associated mood changes and risk for milder forms of depression.

Ruta Nonacs, MD PhD

References

Larsen SV, Mikkelsen AP, Lidegaard Ø, Frokjaer VG. Depression Associated With Hormonal Contraceptive Use as a Risk Indicator for Postpartum Depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023 Jul 1;80(7):682-689.

Leave A Comment