Many women ask whether taking antidepressants may increase the risk for miscarriage or spontaneous abortion. Some, but not all, studies have demonstrated an increased risk of miscarriage among women who use antidepressants. However, it has been difficult to determine whether this increased risk observed in early studies is related to exposure to the medication itself, or whether increased risk may be attributable to exposure to other risk factors, including maternal depression. Many of these studies where to able to separate these two possibilities, as they compared rates of miscarriage in women taking antidepressants to rates in healthy women without a hitory of depression.

A meta-analysis published in JAMA Psychiatry analyzed data from a total of 11 studies assessing pregnancy outcomes in women taking antidepressant medications during pregnancy. This meta-analysis, the largest to date, demonstrated no significant association between antidepressant exposure and risk for spontaneous abortion (odds ratio [OR], 1.47; 95% CI, 0.99 to 2.17; P = .055).

More recent studies have attempted to provide more accurate estimates of the prevalence of miscarriage while taking into consideration potential confounding factors.

In one study, Kjaersgaard and colleagues examined pregnancy outcomes in over one million pregnancies included in the Danish Medical Birth Registry and the Danish National Hospital Registry. Data were assessed for 1,005,319 pregnancies, of which 114,721 (11.4%) ended in a spontaneous abortion. The authors found a slightly increased risk of spontaneous abortion associated with the use of antidepressants: 12.0% in women with antidepressant exposure versus 11.1% in women with no exposure. However, looking only at women with a diagnosis of depression, the adjusted risk ratio (RR) for spontaneous abortion after any antidepressant exposure was 1.00 (95% CI 0.80-1.24). Thus, the researchers concluded that a diagnosis of depression – but not exposure to antidepressant – is associated with a slightly higher risk of miscarriage.

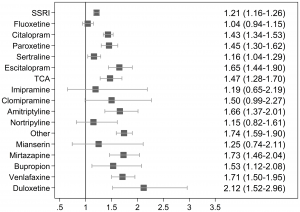

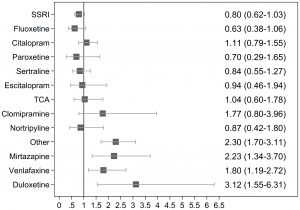

These two figures are a nice depiction of the findings. Figure 1 (one the left) shows the unadjusted risk ratios (RR) for spontaneous abortion after exposure to specific antidepressants compared to the unexposed controls. Figure 2 (on the right) shows the nadjusted RRs for spontaneous abortions after exposure to specific antidepressants among women with a diagnosis of depression, comparing women with and without prenatal antidepressant exposure. At least for the SSRIs, these findings indicate no increase in risk associated with antidepressant exposure.

In unadjusted analyses, less commonly used antidepressants, such as mirtazapine, venlafaxine, and duloxetine, were associated with spontaneous abortions among women with depression. However, the number of women on these medications was much smaller, making the precision of these findings more questionable. Furthermore, it is possible that patients on these medications had more severe or treatment resistant depression, considering SSRIs are often considered first-line antidepressants for use in pregnancy.

Another study from Andersen and colleagues identified all registered pregnancies in Denmark from 1997 to 2010, using the Medical Birth Registry, and all records and the National Hospital Register. Data on SSRI use was gathered using the National Prescription Register. The researchers identified 1,279,840 pregnancies (911,569 births, 142,093 miscarriages, and 226,178 induced abortions).

Of the 22,884 exposed to an SSRI during the first 35 days of pregnancy, 12.6% (2,883) ended in miscarriage compared with 11.1% among those who discontinued SSRI treatment. The adjusted odds ratio (OR) of having a miscarriage after exposure to an SSRI was 1.27 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.22-1.33) compared with unexposed. However, when they looked at women who discontinued SSRI treatment 3-12 months before pregnancy, they found that this group also had an increased risk of having a miscarriage compared to unexposed women (OR=1.24, 95% CI 1.18-1.30). Thus, they concluded that having a diagnosis of depression, rather than use of an antidepressant, increases risk for miscarriage.

Based on these findings, we can conclude that for women taking SSRI antidepressants prior to pregnancy, stopping or tapering off the antidepressant does not appreciably affect their risk of miscarriage. Whie the data is less clear regarding risk in women taking SNRIs and mirtazapine, it appears that the impact of these medications on risk for miscarriage is very small. However, we do know that stopping antidepressants during pregnancy significantly increases the risk of depressive relapse.

Ruta Nonacs, MD PhD

References:

Andersen JT, Andersen NL, Horwitz H, Poulsen HE, Jimenez-Solem E. Exposure to Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in Early Pregnancy and the Risk of Miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Sep 5.

Johansen RL, Mortensen LH, Andersen AM, Hansen AV, Strandberg-Larsen K. Maternal use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of miscarriage – assessing potential biases. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2015 Jan;29(1):72-81.

Kjaersgaard MI, Parner ET, Vestergaard M, et al. Prenatal antidepressant exposure and risk of spontaneous abortion – a population-based study. PLoS One. 2013 Aug 28; 8(8):e72095.

Ross LE, Grigoriadis S, Mamisashvili L, et al. Selected Pregnancy and Delivery Outcomes After Exposure to Antidepressant Medication: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70(4):436-443.

Related Posts:

Use of Antidepressants Does Not Increase the Risk of Miscarriage